The Grid

Hello Weavers,

I am returning to my blog after a long hiatus. It turns out that my subscriber list was lost due to me mistaking an IMPORTANT email for spam and causing “them” (Mailchimp – probably not an evil human, more likely an uncaring algorithm) to delete my list. I was a bit downhearted as a consequence, but have decided jump back in. And there are some fun things afoot.

My pattern-writing partner and I have created a new website called Groundweave.com. It will be different from this site because we are working on it together and because the mission is slightly different. Plainweave will remain my personal weaving blog, while Groundweave is our mutual effort. We will take turns writing monthly posts, as well as adding resources like sett charts, glossaries and information for weavers who buy our patterns. I hope you take a peek.

Meanwhile I am going to post my first Groundweave blog post here in case there are still some readers left after my long blog negligence.

The Grid

I recently saw the show Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was a thoughtfully curated, big, multi-discipline show that included pieces by many of my artistic idols such as Anni Albers, Gunta Stölzl, Lenore Tawney, Agnes Martin, Paul Klee, Ruth Asawa, and Sheila Hicks as well as many artists that I didn’t know much about like Ed Rossbach, Andrea Zittel and Olga de Amaral. There are woven, knitted and knotted pieces, assemblages, baskets, paintings and photographs. I was moved by the show and thought I would use this post to try to parse some of my reactions and thoughts focussing on (surprise!) the woven pieces and the weaverly paintings. I could look at Anni Albers’ Black White Grey for hours thinking about how she managed to make such a dynamic woven piece with such a limited palette and simple, geometric forms.

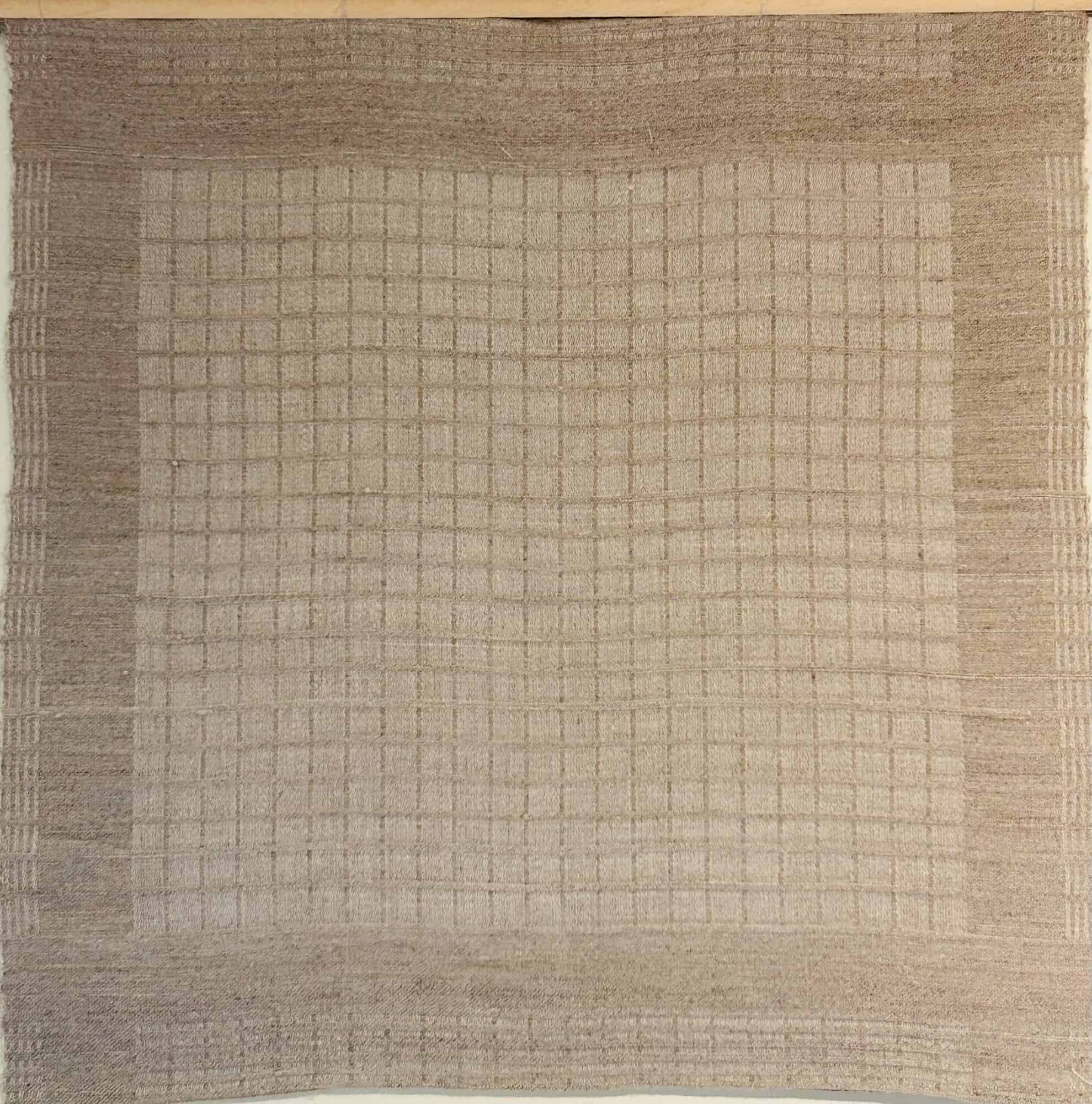

Anni Albers, Black White Grey, 1927/1964

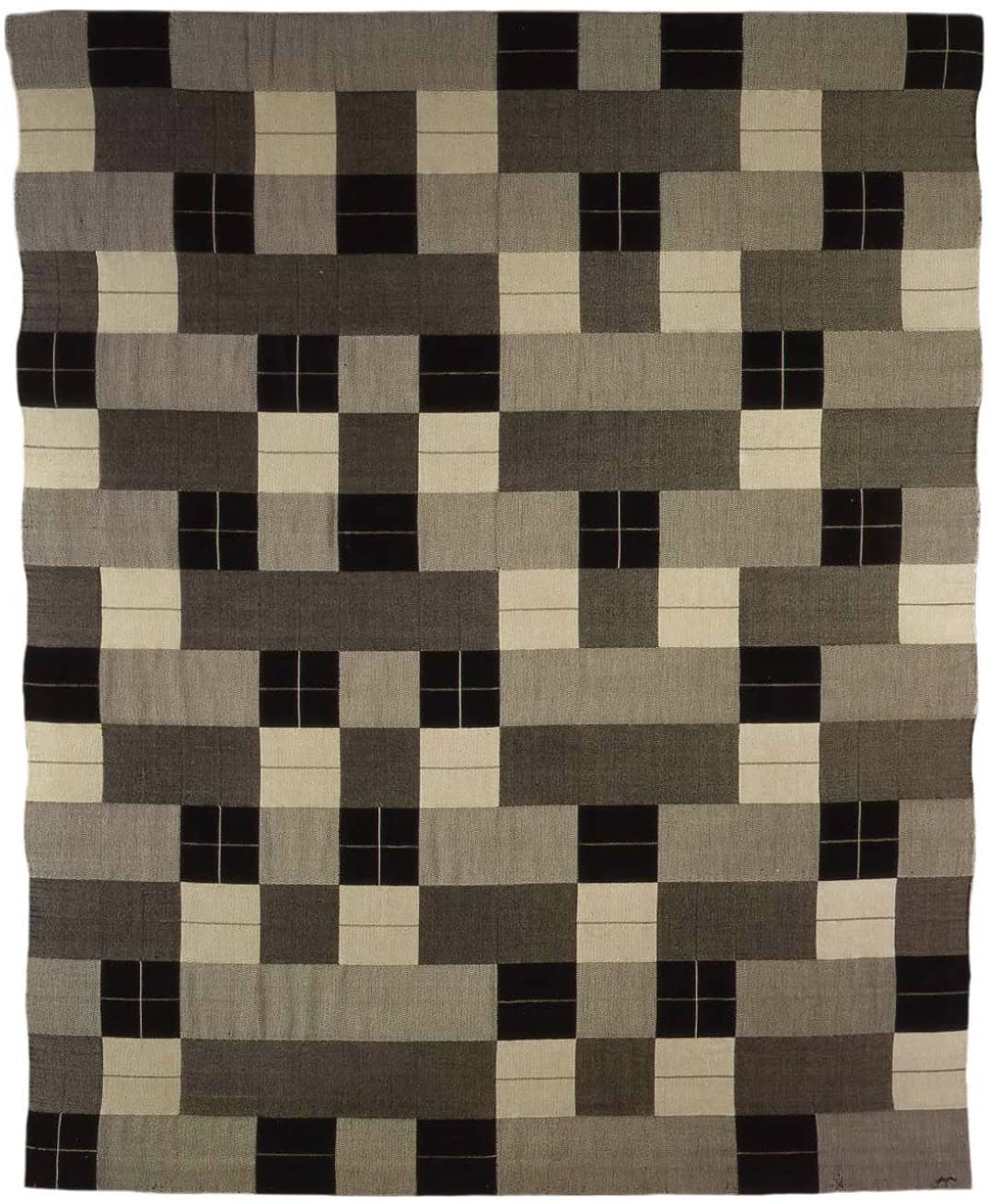

Olga de Amaral, Transparencia dorada, 1971/1984

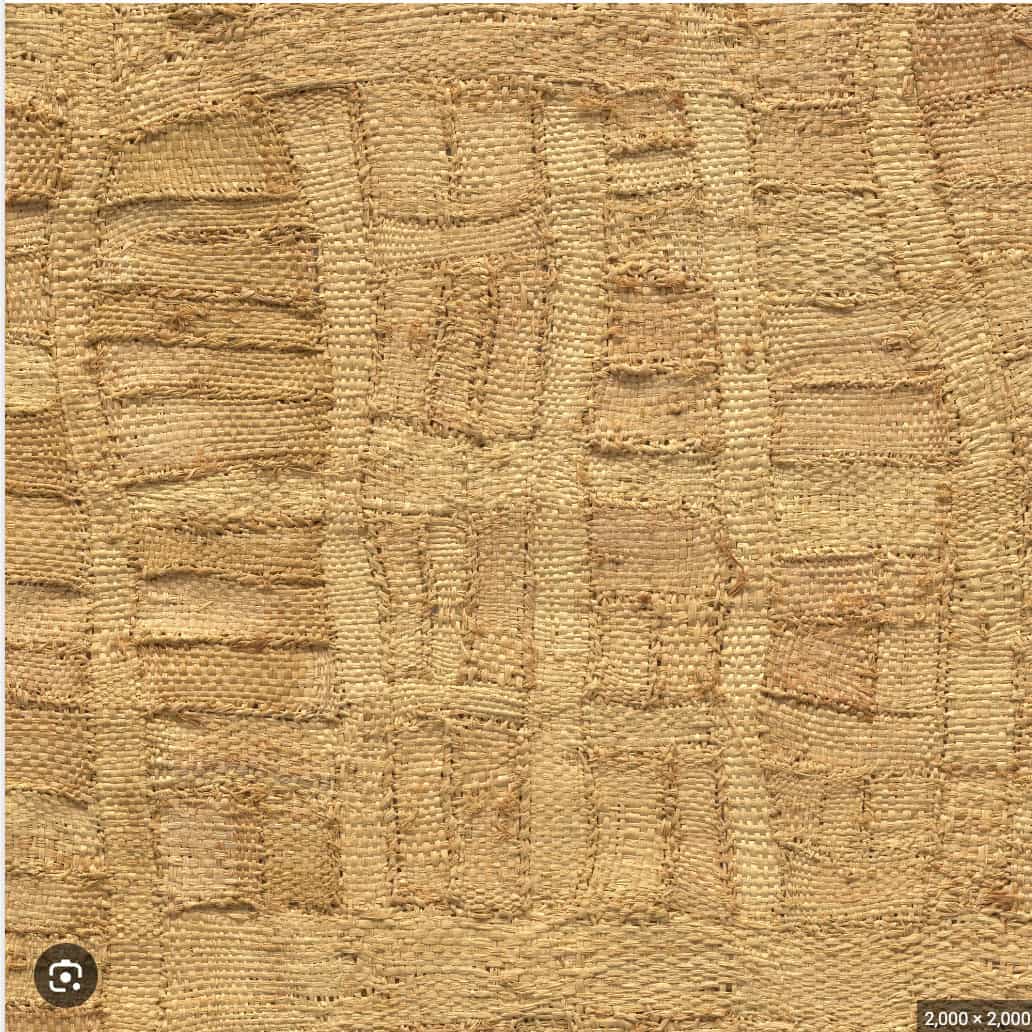

Black White Grey along with a “meta” piece by Olga de Amaral and Ed Rossbach’s piece Tapestry were my three favorite woven pieces.

Ed Rossbach, Tapestry, 1964

And Agnes Martin’s Untitled is a piece that has fully captured my imagination. It’s is oil on canvas but clearly has a connection to the weaving (Martin was roommates with Lenore Tawney at an early point in her career).

Agnes Martin, Untitled, 1960

I was trying to assess what it is about these pieces that captivated me, and I believe the “grid” may be the answer. We weavers are set up with a system of parallel lines (warp) as our canvas. If we are weavers, we obviously find something enticing in that system. Coming from a family of artists, I personally loved the restriction of the grid. The freedom of a blank canvas and a palette of paint was daunting, but the loom and it’s “limitations” gave me a sense of creative freedom.

One of the things I admire about the pieces I have chosen is that they have an obvious love for and connection to the grid, but have magically, through mastery and vision, made that system of parallel and perpendicular threads important and moving. The grid is present, but not a limitation for these artists. Albers’ piece adheres strictly to the grid, but brings excitement and movement with the placement and repetition of the blocks. Olga de Amaral uses scale to create a giant basket weave in which the floats are unconfined and shift to create waves and movement. Ed Rossbach uses discontinuous weft technique to disrupt the grid while still invoking it. From a distance it appears to be pieced cloth, but one is surprised upon closer inspection to see that it is a one-color tapestry.

We weavers are, of course, destined to defy the grid, and I have taught a course on structures that help us do that, but when discussing my relationship with “the grid” with my husband recently, he said, “maybe defy not deny” should be your mantra.

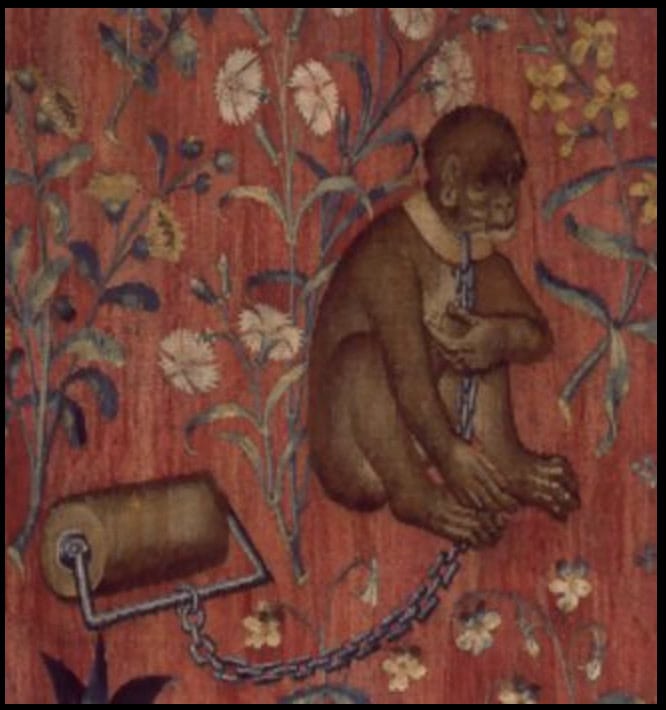

Anni Albers writes about “the grid” and how she preferred the pre-colombian textiles which honored the grid in contrast to the European tradition of tapestry in which weavers used great ingenuity to subvert the grid and mimic the freedom of paint on canvas.

(Precolombian art, Nazca civilization: fragment of fabric with zoomorphic representation. 100 BC-800 AD. Goteborg, ethnographic museum)

Detail of the Tapestry of the Lady and the unicorn, Musée de Cluny, Paris, circa 1500

I think that Albers’ admiration of the pre-Colombian weavers was in part because their bold, graphic style appealed to her modernist eye, but it would be hard for any weaver not to admire the immense skill and inventiveness that the pre-Colombian weavers brought to their looms.

But back to the grid. Albers’ work which was bound by the woven grid was being designed and made during an era that was eschewing extraneous ornamentation, breaking down art and architecture into simplified shapes and forms and believing that (after the catastrophic world wars) the new system would truly save the world from the excesses of emotion that had caused the horrors of WWI & WWII. The weight of these beliefs is imbued (I believe) in the work of Albers and Stölzl and it is not surprising that their work is still relevant and valued.

I wish I believed in an aesthetic that could save the world. But even without that conviction, this show was an immense inspiration. I am a utilitarian weaver, but it was truly gratifying to see high-impact woven art and to feel the power of our humble grid in the hands of masters.

Gerri Barosso

Thanks! I appreciated the opportunity to read your insights. Our weaver’s grid isn’t confining so much as defining. Looking forward to Groundweave.

Elisabeth Hill

Hi Gerri,

Good to hear from another grid gazer!

Judith Larseb

Welcome back. Glad to participate.

Judith Larsen

Welcome back

Elisabeth Hill

Hi Judith,

Thanks for your comment, and super glad to know that I am not just musing into the void:))

Janie Gummer

So glad you are back – I really enjoy your blog

Elisabeth Hill

Hi Janie, thanks for your comment. So glad to have you as a reader.

moni

Pleaase take me into your Blog Post

Elisabeth Hill

Thank you, I will!

Dianne Dudfield

Always enjoy your musings and weaving so Welcome Back.

Elisabeth Hill

Thanks Dianne, I am a textile stalker on IG – always looking – rarely commenting, but I love your work, and appreciate your kind words!

Tory

Ha!! there I was, pondering honeycomb (sort of: think honeycomb with its finger stuck in a light socket, OR, a rag. Absolutely nothing to do with grids) & ‘somehow’ your blog came up 😉 Of course I hadn’t visited in some time, thinking your were (always are) up to something or another else (also & always), and the blog was (and is), a point of reference if not ‘current’. May the grid be with you! (until deflection of one sort or another ‘distracts’ you). Carry on!

Elisabeth Hill

Ha! I’m in a honeycomb via dimity tunnel at the moment “great minds, etc.” or “great fanatics, etc”